Myanmar Peace Museum’s founder Ko Sai: “Censorship amplifies the message”

Interview and photos by Mercury and Shwe Zin Soe // Edit by Shwe Nakamwe At the heart of Bangkok’s cultural district, an exhibition by the Myanmar Peace Museum was unexpectedly thrust into the spotlight when Chinese government pressure led to its partial censorship. What had begun as a modest, self-funded project curated by Myanmar artist-activists, Sai and his partner, quickly evolved into a powerful case study of complicity – between authoritarian regimes, cultural institutions, and global trade networks.

“We never had curatorial funding,” Sai explains, “this was activism from our own pockets.”

Ironically, the exhibition’s suppression amplified its message that authoritarian regimes collaborate not only in arms and politics but in silencing the stories of oppressed communities – from Myanmar’s resistance movement to the struggles of Uyghurs and beyond.

Sai recalls the timing of the Bangkok opening vividly. “Because Cambodia and Thailand engaged in significant border conflict, people were not in the mood for celebration. A 7-Eleven was destroyed, some people died. So the crowd wasn’t as large as expected. But honestly, we preferred it that way – manageable, respectful. Many people still came on the 24th and 25th before the authorities started to take things down.”

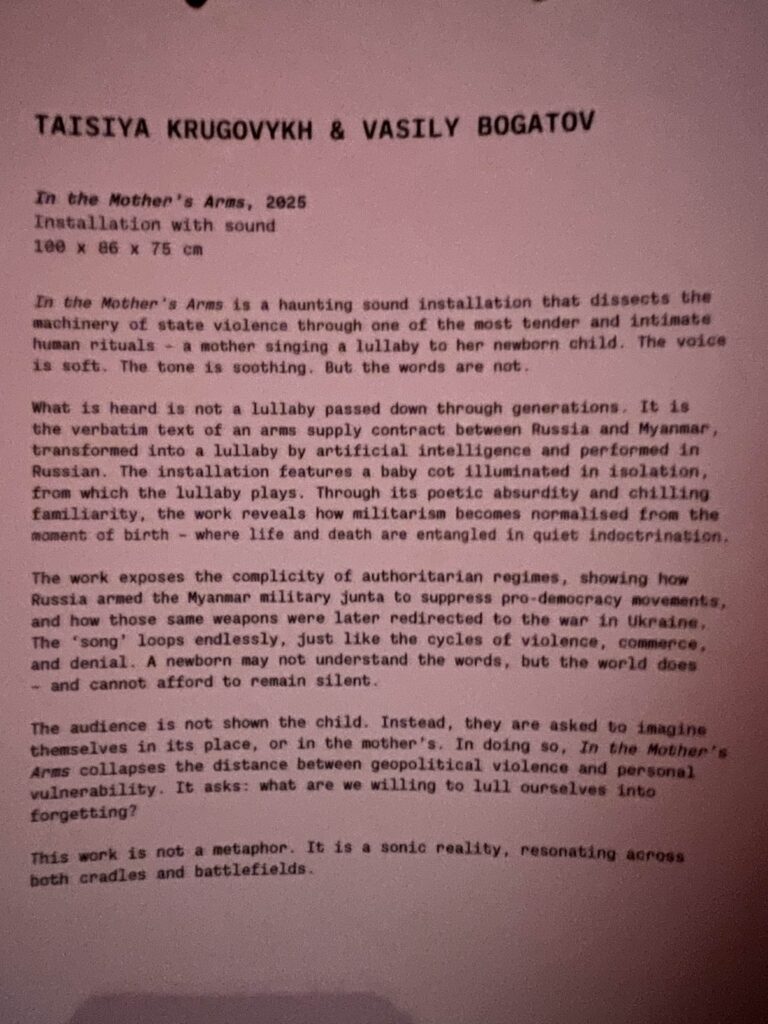

The exhibition, designed as a living testament to complicity, was never meant to be an ordinary cultural event. It documented how the Myanmar junta continues to survive with the support of authoritarian partners abroad. Visitors to the exhibition encountered works exposing hidden trade routes, political bargains, and cultural erasure – revealing how oppression is sustained, and made ordinary.

The act of censorship itself however, carried out under order from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), provided the most powerful lesson. For Sai, the experience underscored a hard truth: authoritarian regimes cannot tolerate oppressed communities standing together. “The exhibition itself proved the point. These networks don’t want us to stay united. But that shows we are on the right track – we have to keep moving forward.”

Despite the setback, the curators refuse to retreat. What was initially envisioned as a biennial show in Bangkok is now in demand internationally. “People want the exhibition to travel, because of what the CCP did,” Sai says. “Of course, we had hoped to stay in Bangkok, to bring friends for personal tours, to explain the works ourselves. It is sad we cannot do that anymore. But in another way, censorship has become part of the exhibition. It revealed the very complicity we wanted to show.”

As the Myanmar Peace Museum looks ahead, their goal remains unchanged: to ensure Myanmar’s struggle is not forgotten and to make it resonate within global movements for freedom. This exhibition, though silenced in Bangkok, has already spoken louder than its curators ever imagined.

A Name in Black, A Story in Silence

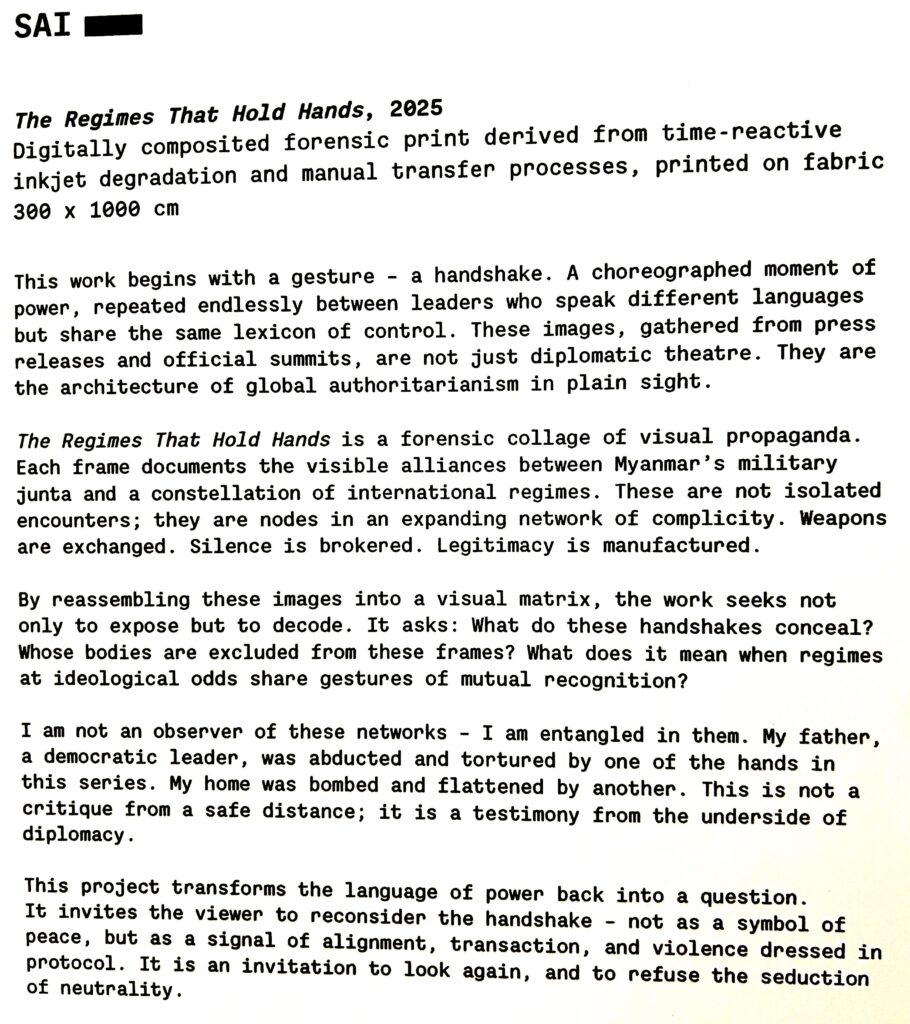

For Myanmar artist-activist Sai, even his name is a battleground. “Sai” is not a full name in itself, but a title—something like “Mister,” or the way Thai people use “Lung” or “Pee.” Before the 2021 coup, he used his legal name freely as both his personal and artist identity. But that changed the day Myanmar’s military seized power.

On February 1, 2021, his father—a Shan State chief minister—was abducted and taken hostage. His mother was placed under house arrest. Nearly five years later, his father remains in isolation in a maximum-security prison, sentenced to 16 years on corruption charges widely seen as politically motivated. For Sai, the cost of resistance became deeply personal.

“If I used my real name now, it would put my parents in even greater danger,” he explains.

Since the coup, he has adopted “Sai” as his sole artist name, presenting it visually as “Sai” followed by a black block. The block functions as both erasure and camouflage: an act of self-censorship, but also a protective shield. “There are many people with the name Sai. If someone asks, ‘Do you know Sai?’ it creates confusion. That ambiguity actually protects me.”

This practice carried into Bangkok’s controversial exhibition. While the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) later accused the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) of “distorting reality,” it was Sai himself who had already chosen to censor his own name for survival. BACC adopted the same black-block aesthetic throughout the show—not to erase artists under CCP orders, but to make censorship itself visible.

Below are some of the texts that were redacted after the visit by the Chinese embassy, following Sai’s name style:

Misunderstood Messages

Before the exhibition opened, Sai and his team advised BACC to remove sensitive country names, anticipating problems. But local staff reassured them: “It’s okay, this is for educational purposes only.” That trust would soon prove misplaced.

The CCP accused the show of promoting “unmarketable ideas” such as Hong Kong independence, Tibetan culture, and what they called the “Eastern Turkistan movement” — a phrase carefully avoiding the word Uyghur. On August 5, Chinese representatives even thanked BACC for “complying with the One China policy.”

Yet the works themselves told a different story. The Hong Kong piece the CCP flagged as separatist was actually about surveillance—a playful “Anti-Spy Spy Club” inviting viewers to “spy on the spies.” Using the language of “Big Brother,” it pointed at authoritarianism in general, not Beijing specifically. “The CCP didn’t fully understand the exhibition,” Sai notes.

Selective Erasures

Some names were stripped, but most artworks remained. The Hong Kong artist’s credit was removed, though his piece stayed. The Uyghur artist’s contribution remained intact. Tibetan works suffered more — with references to the Dalai Lama, national flags, and some video installations cut — but their core still survived.

The irony, Sai points out, is that none of these artists are Chinese citizens. The Uyghur artist is based in France, the Hong Kong contributors live in the UK, and the Tibetan artist is Tibetan-American. “That’s what makes it so absurd,” he says. “The host country and host institution still complied with CCP demands, even though the artists were not Chinese citizens and their works were shown outside China.”

Overlooked Resistance

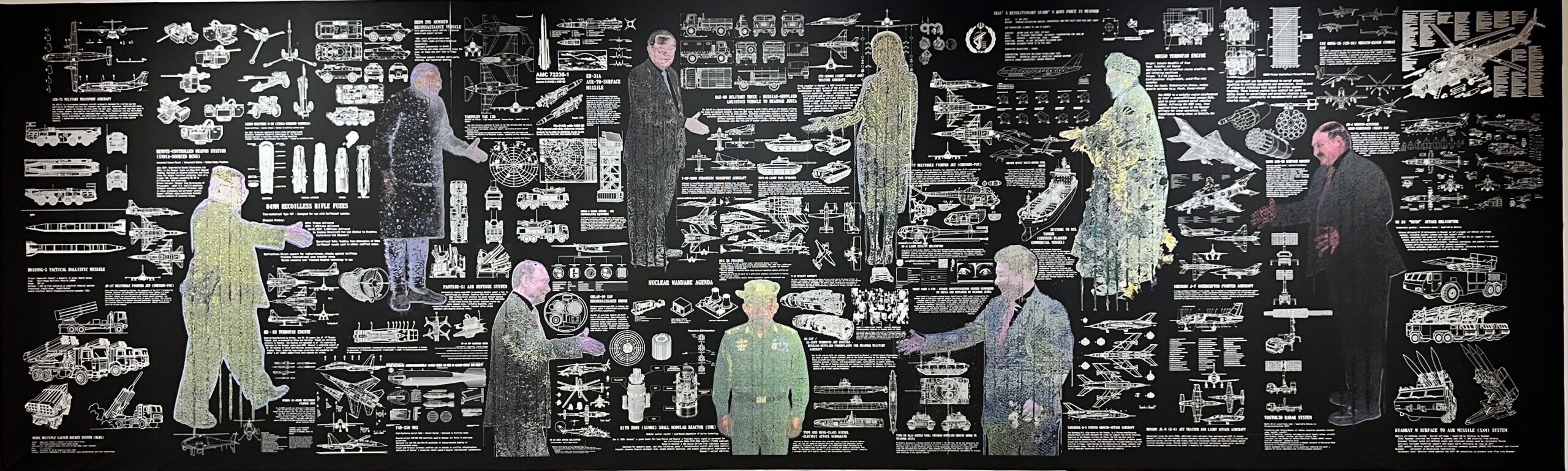

Sai’s own pieces, meanwhile, were untouched. He can only speculate why. “My work is entirely based on public information—UN reports, human rights research, data on weapons and technology. I just compiled what was already there, sometimes finding new connections. I wasn’t leaking anything secret.”

Perhaps, he suggests, the CCP saw his pieces as less threatening. Or perhaps it was because, as a Myanmar artist, his country is already under China’s heavy influence. Or maybe, he shrugs, they simply missed it. “I don’t really know—but it’s interesting.”

From Outsider to Curator: The Making of an Artist-Activist

For Sai, the path into art was not straightforward. Growing up in Lashio, he was fascinated by photography from a young age but never had the means to pursue it. “My family couldn’t afford a camera. Only my uncle had this plastic Protech camera, and whenever I visited, I used it,” he recalls. At age 23, after borrowing money from his mother, he finally bought his first camera and began to teach himself.

But artistic curiosity clashed with family expectations. Sai’s father, who briefly performed political comedy as a student alongside Burma’s famous satirist Zarganar before giving it up to become a dentist, discouraged any pursuit of art. That short-lived comedy career was the only artistic activity in the family, and it left no tradition for Sai to follow. “He always stopped me when I tried to draw or play piano,” Sai says. “He told me we had no background as artists, so it would be very hard.”

Later, living far from home gave Sai the freedom to learn on his own terms. Photography opened more than artistic practice – it connected him to Myanmar’s turbulent realities. He first tried his hand at documentary work, but unlike his photojournalist peers, his strength lay elsewhere. “I admired them, but I didn’t have the skill to survive as a documentary photographer,” he admits. Instead, he began exploring photography as a deeply personal medium, capturing his “mental landscape” as an outsider caught between ethnic identities. With a Bamar father and a Shan mother, he was never fully accepted by either community. “Shan people hate Burmese, understandably. Burmese don’t hate Shan, but they see us differently. I was always in between.”

That project – rooted in his lived experience of alienation – won him recognition at the Yangon Photo Festival, where he received an award from Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. This validation marked a turning point, and though he remains critical of the festival itself, Sai’s work had moved from private expression to public impact.

He found himself drawn into curatorial work. Helping with the Yangon Art and Heritage Festival led to his first major exhibition as co-curator in 2019: Building Bridges at the historic Tourist Burma building. Bringing together 10 Myanmar artists alongside international collaborators, the exhibition broke new ground by embracing social themes, human rights, and augmented reality technology. Critics hailed it as one of the year’s most important shows.

Sai describes curating as an extension of activism, not a career. “It was a no-money job, but we were proud,” he says. What began as personal exploration through photography had evolved into collective projects aimed at opening space for dialogue and resistance. Even before the 2021 coup, he was learning firsthand how art in Myanmar existed under constant negotiation—with gatekeepers, with politics, with silence.

That hard-won experience would become the foundation for his next, and most dangerous, chapter: transforming art into testimony against authoritarian complicity.

Exile, Resistance, and the Search for Connection

Leaving Myanmar after the coup was never part of Sai’s plan, but exile became inevitable. In Thailand, a new rhythm of political life emerged, not marked by hierarchy or party politics but by youthful determination. “Life in Thailand was exciting,” he says. “We don’t care about politics, positions, or hierarchy. We just want the military gone. And it’s the young people driving this revolution, not the old ones fighting for seats abroad.”

For a Myanmar passport holder, returning to Thailand was risky. Yet Sai insists it was necessary for his mental health. Being back allowed him to reconnect with recently released political prisoners in Mae Sot and Chiang Mai, as well as families who had fled persecution. He began documenting their stories, building networks, and knocking – sometimes forcefully – on the doors of human rights organizations. “I didn’t care if I was rude,” he laughs. “I just wanted to connect. To connect, to connect.”

The more he listened, the more he realized how little support existed for political prisoners in exile. That realization pushed him deeper into advocacy work, eventually linking him with groups like OHCHR. What began as personal survival gradually transformed into collective responsibility: amplifying the voices of Myanmar’s displaced and imprisoned.

Yet his vision extends beyond Myanmar. From Hong Kong protests to Ukraine’s resistance, Sai recognized a troubling absence: Myanmar was missing from the global map of solidarity. “At a Hong Kong protest in London, I saw Ukrainians standing with them. And I thought: where are the Myanmar people? Why are we invisible?” This question has since become central to his mission.

Through the Myanmar Peace Museum, which he co-founded with his partner, Sai seeks to weave Myanmar’s struggle into the fabric of international movements. “We want Myanmar to be relatable,” he explains. “People think it’s a faraway country with nothing to do with them. But half of China’s rare earth imports come from Burma. Suddenly, they realize: Myanmar matters.”

Exhibitions, testimonies, and cultural narratives are his chosen tools. From plans to bring their work into the UK Parliament to earlier talks at the U.S. Congress, Sai sees the museum as a bridge that links Myanmar’s silenced communities with a world that too often forgets them.

“We don’t want to be another Syria,” he warns. “Oppressed communities – Uyghurs, Tibetans, Rohingya, and others – are already being erased. If we don’t stay relevant, Myanmar will be forgotten too.”

Below, the song “Normal” by Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi, who has been repeatedly arrested for his civil and artistic activism during the Salehi was arrested during the “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom) movement.

The Long Arm of Censorship

Authoritarian regimes rarely stop at their own borders. For Sai, the closure of the Bangkok exhibition was not an isolated event but part of China’s larger global pattern of the transnational repression of art, speech, and dissent. “The CCP has been doing this everywhere,” he explains. “Even in France, even in the UK. They already have underground police stations in Europe. Even here, in the UK, they set up things disguised as computer centres, but they are basically surveillance outposts.”

One case stands out in his memory: the Chinese dissident artist Badiucao, known for his sharp political cartoons. In 2023, Badiucao exhibited in Warsaw, Poland, with works critical of the Chinese Communist Party. Beijing pressured the Polish government to shut it down. But unlike Thailand, Poland refused. “The Ministry of Culture was contacted by the Chinese embassy,” Sai recalls, “but they said, ‘thank you for your request, we don’t comply.’ The exhibition went on.”

The contrast was striking. In Thailand, the authorities caved under Chinese pressure, citing concerns over trade and economic relations. In Poland, the exhibition stood, unbowed. The lesson, Sai argues, is that censorship ultimately depends on the host country’s willingness or unwillingness to compromise. “Every time you compromise, you trade something away. Sometimes it is freedom of expression. And when that is gone, what is left of a nation’s foundation?”

For Sai, this is not just about Myanmar’s struggle, or even China’s reach. It is about the future of global freedom itself. “With technology and AI on China’s side, maybe one day our voices will be censored automatically. Maybe we won’t even be able to say certain words – they will just become a beep.”

He sees troubling signs already in the UK. Plans for a massive new Chinese embassy near Tower Bridge in London were met with little local resistance, with Hong Kongers leading the protests while most British citizens stayed home. “As long as people don’t recognize China’s influence and surveillance, it will be very difficult,” he warns.

The fight is not just for Myanmar’s visibility but for the very space in which oppressed people can speak, share, and resist. “Freedom of expression is not something you trade lightly. Once you give it up, piece by piece, you may find there is nothing left.”

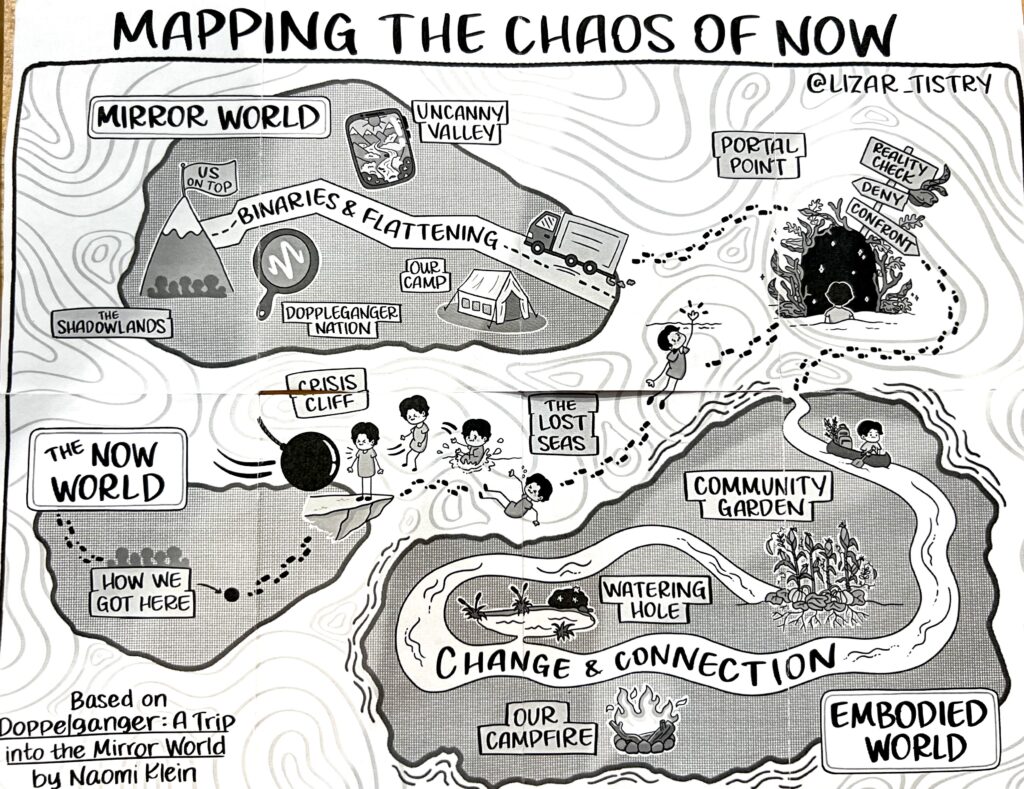

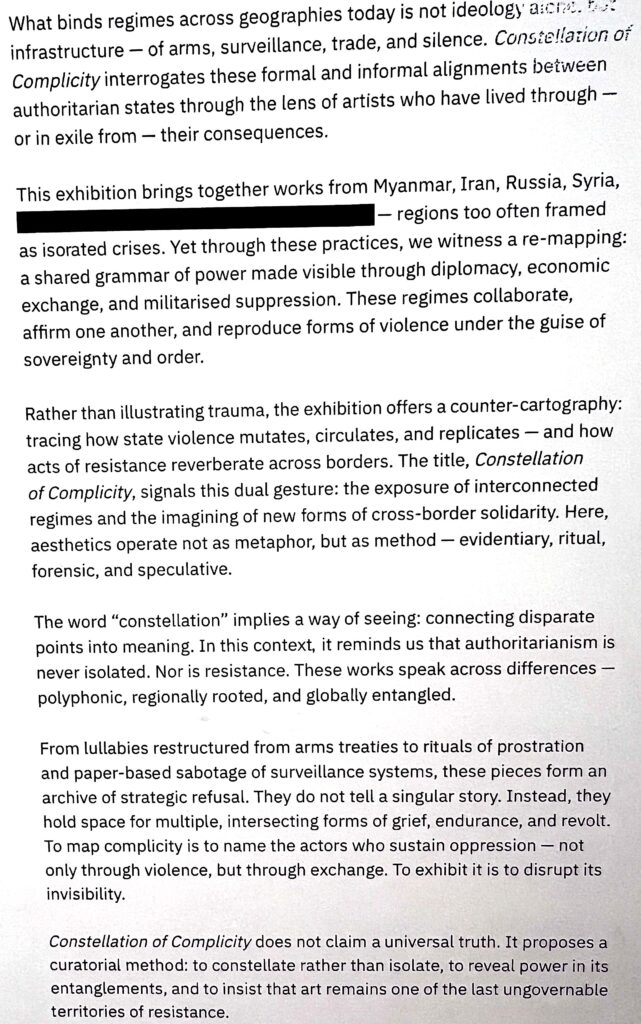

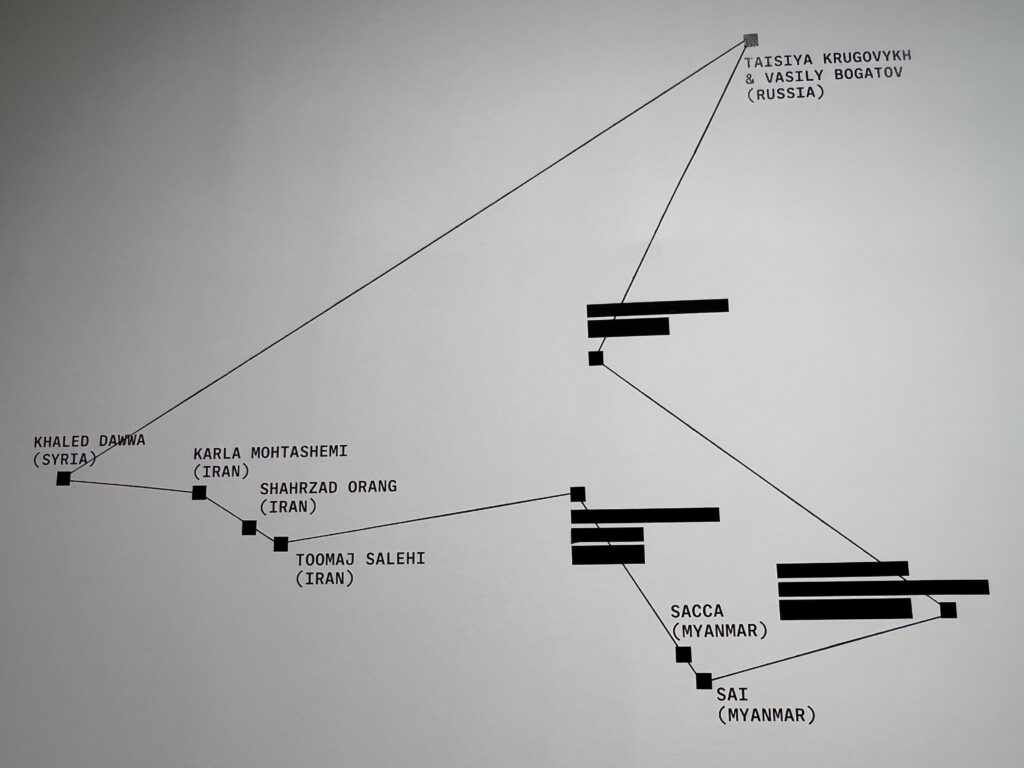

Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machinery of Authoritarian Solidarity

Organised by Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA)

Project Supported by Emergent Art Space (EAS) and JINA Alliance

Curated by Myanmar Peace Museum

When >> 24 July – 19 October 2025

Where >> Main Exhibition Gallery, 8th Floor, BACC

Who >> List of artists [uncensored]